Translate

Monday, August 29, 2016

Robert Rauschenberg, Artist, b. 1925, d. 2008, USA

Scrape (Hoarfrost Editions)

1974 76 x 36 inches

Offset lithograph transferred to

collage of paper bags and fabric

Edition of 32

Robert Rauschenberg worked in a wide range of mediums including painting, sculpture, prints, photography, and performance, over the span of six decades. He emerged on the American art scene at the time that Abstract Expressionism was dominant, and through the course of his practice he challenged the gestural abstract painting and the model of the heroic, self-expressive artist championed by that movement.

In his landmark series of Combines (1954–64) he mixed the materials of artmaking with ordinary things, writing, “I consider the text of a newspaper, the detail of photograph, the stitch in a baseball, and the filament in a light bulb as fundamental to the painting as brush stroke or enamel drip of paint.”1 In Bed (1955), for example, he covered a large wall-mounted board with a pillow and patchwork quilt which he then marked with graphite scrawls and exuberant lashings of paint, the latter perhaps an ironic nod to Abstract Expressionism.

Born in Port Arthur, Texas, Rauschenberg studied at a variety of art schools including the experimental Black Mountain College outside of Asheville, North Carolina, where the artist and former Bauhaus instructor Josef Albers was his teacher. There, his mentors and collaborators included the composer John Cage, the artist Cy Twombly, and the choreographer Merce Cunningham, with whom he would collaborate on more than twenty dance compositions. Rauschenberg’s engagement with performance was enduring and a defining influence in his work. As his career began to gather steam in New York in the mid-1950s, he also began a crucial dialogue with the artist Jasper Johns that shaped the work of both: together the two artists pushed each other away from defined models of practice towards new modes that integrated the signs, images, and materials of the everyday world.

Photography and printmaking were two of Rauschenberg’s abiding interests. In the 1958–60 seriesbased on the thirty-four Cantos of Dante’s Inferno(346.1963.1-34), he used a solvent to transfer photographs from contemporary magazines and newspapers onto drawing paper. The series is emblematic of a lifetime of experimentation with the ways the deluge of images in modern media culture could be transmitted and transformed.

Text source Museum of Modern Art

William Kentridge, Artist

William Kentridge, Remembering the Treason Trial, 2013. Lithograph: 63 panels hand printed on a Takach litho press from aluminum plates in 3 runs on 145 gsm Zerkall 100% cotton. Overall size: 76 x 70 3/4 inches (193.04 x 179.71 cm) Panel size: 11 x 7 3/4 inches each (27.9 x 19.7 cm each). Image courtesy of William Kentridge.

"...his job is to “make drawings not to make sense.”2 That he does make sense – and so much of it – is due in large part to his willingness to abandon it. Which is to say: to throw it in the air like a cascade of woodchips. Or a pile of leaves (the tree’s mingling with the book’s, mind you.) Or the pieces of a large puzzle – which the fragmentary, taped-together lattices of his tree studies increasingly began to resemble. And even as he reassembles these fragments in new and innovative ways, he won’t let us forget the fragility with which they are held together, or their urge to fly backwards into the anarchy of the scatter. Is this force entropy, I began to wonder, or rather, our attraction to the promise of the unmade and the unbuilt, the unresolved and the disunified? Our urge to “unthink” the thought we just had. In any event, it places us into a universe of endless bits and pieces, only some of which submit to being glued back together. To be sure, by the end of Second-Hand Reading, the allure of thought’s tiniest and most scattered branches had quietly trumped the enticements of unity. Or to restate the point: perhaps not being able to see the forest for the trees is, after all, a good thing."-an excerpt from an article written by Leora Maltz-Leca, Associate Professor of Contemporary Art History of Art & Visual Culture at the Rhode Island School of Design. Source link is Invisible Culture

SaveSave

William Kentridge, Artist

William Kentridge (South African, b. 1955). More Sweetly Play the Dance, 2015.

Digital scan from the master Apple ProRes file. George Eastman Museum, gift of the artist.

source link is Eastman Museum

Sunday, August 28, 2016

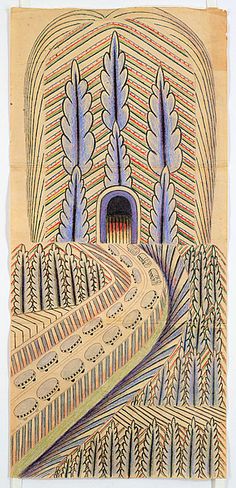

Martin Ramirez, b. 1895 Mexico, d. 1963 USA

UNTITLED (Stag)

Martín Ramírez (1895–1963)

Auburn, California

c. 1948–1963

Crayon and pencil on pieced paper

56 x 29 1/2 in.

Collection of Selig and Angela Sacks

Photo by Gavin Ashworth

Martín Ramírez (1895–1963)

Auburn, California

c. 1948–1963

Crayon and pencil on pieced paper

56 x 29 1/2 in.

Collection of Selig and Angela Sacks

Photo by Gavin Ashworth

Saturday, August 27, 2016

LOOK

I am compiling a list of artist blogs and blogs that feature artwork. If you come across a blog that you think should be on my list, leave a message in the comments or e-mail me at lmongiovi@flagler.edu

Green Lashes

Green Lashes

Saturday, August 20, 2016

Carmen Argote, Artist

In-Line (magnet drawing)

2011

About the Piece

This work composed of chicken wire hexagons and copper mesh is held together by hundreds of small magnets. Each magnet holds a component to the canvas surface. This works looks at systems of organization such as strands and lines to create an image created by lining up these small hexagonal mechanically woven wires. With these works, I explore the idea of where a drawing can happen. I envision the space between the magnet and the chicken-wire piece to be the place where the drawing happens.

I envision these as freestanding, allowing the viewer to walk around the work and see the magnetic elements inherent in the work.

Material: chicken wire, magnets, canvas

Dimensions: 6' x 7' x 2"

Above image: A series of sculptures inspired by a simple laundry folding tool, co-opted as a sculptural form. These sculptures are reminiscent of both architectural structure and the physical movement which translates loose fabric into folded structure. They embody the ritual of folding, a process of layering over onto itself, so that one part covers another. The folded structures, like the installation, are of a human scale, yet transform into architectural models through repetition and play.

Material: Paper mache, paint, cardboard, tape, muslin

Dimensions: Variable

Artist Statement

As a multidisciplinary artist working in installation, I explore notions of home and place, interacting with architecture to reflect on personal histories and my own immigrant experience. I work with places and materials that surround me, utilizing local resources as points to expand from. My practice uses the act of inhabiting as a starting point, allowing the work to take form as I respond to a space, materials and ideas developing from my own experiences and relationships to a site.

I work from an intimate and personal place, using shared experiences to connect the spaces that house us to notions of home and self. Often working with family, I explore our common immigrant experience as a layered, multigenerational, transnational experience that is echoed though shared memories, traumas, and aspirations, extending outward from the intimate space of home.

Architecture for me exists apart from the physical structure, in familial myth, in class structures, in shapes, and as an imprint acting upon the body. My interest in the shape of spaces and in the layout as a visual language for expression developed in childhood from looking at my father’s architectural drawings of houses he wanted to build.

Orit Hofshi, Artist

My practice is primarily based on drawing and printmaking, though I frequently experiment and disregard what would be labeled as common formalistic conventions.

Much of my work is focused on the relation between nature and social occurrences. I spend a great deal of time in various natural settings and am attracted to extreme and rugged landscapes, taking numerous photographs, which nourish my thinking and processing in the studio. The landscapes are typically proposed as places, occupied and unoccupied, touched and untouched, rarely fully committed in a specific context. In such dramatic natural contexts I find an emphasized sense of evolution, time and struggles, not only as records of natural phenomenon but also as reflections of human history.

My work process is characterized by the consistent preoccupation with the dimension of time. I am constantly searching for ways of making time palpable: personal time, the present time, historical time. Calendric time as well as geological, environmental and human activity remnants’ time – examining these different temporal dimensions vis-à-vis the universal temporal dimension, a dimension that may exceed the limitation of human understanding. Such a realization may serve to undermine our sense of self-importance, our tendency to place our own existence at the center, our own hubris.

SaveSave

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)